Exhibition Strategy of Ethnic Museums under the Multicultural Policy in Singapore

任 東昱(韓国外国語大学校大学院 グローバル文化コンテンツ学科)

1.Hidden Intentions in the Museum Exhibitions

Museum serves as a backstage and also a tool for communication between space and visitors, concretely exhibits and spectators. Because of size, cost and management, it is suitable if the project is constructed or operated for a group propaganda rather than personal promotion. Messages intended to be delivered through the museum are often expressed in a way of 'exhibition'. An exhibition can be defined as "the result of the action of displaying something, as well as the whole of that which is displayed, and the place where it is displayed."[1] 'Displaying' in this context entails arranging or unfolding objects. This means that the number of objects is not limited to one or two, and the visitors do not stay and observe in one place, but migrate with the passing of time and proceeds along the moving line or making a new route.

Considering these movements of sorting and ordering of objects is similar to the process of 'storytelling'. The goal of storytelling is to make people empathic with the progress of the story by rearranging elements according to author’s intention. If there is a museum that shows the history and status of a particular group, it is better to organize the exhibition there as a main character and show the process of his achievement beyond hardship. This paper aims to understand the hidden intent of communication by analyzing exhibition strategies of ethnic museums in Singapore, a multi-ethnic country.

[1] André Desvallés & François Mairesse, Key Concepts of Museology, Arman Colin, 2010, p.35.

2.Multi-ethnic Social Structure of Singapore

Singapore is an island country in the narrow strait between Southeast Asia's Malay peninsula and Sumatra's Indonesian island. From 1528, Johor Sultanate occupied Singapore and joined hands with the Netherlands to control the Melaka and Singapore.[2] Singapore occupied its own position since the opening of Sir Stamford Raffles, who works for the British East India company in 1819. Singapore's population now consists of 74.3 percent of Chinese, 13.4 percent of Malay and Indonesian, 9 percent of Indian and 3.2 percent of others.[3] Among the other groups, it is Eurasian, a mixed race between Europeans and Asians, that forms its own community.

These four ethnic groups have lived in different districts since the opening of Singapore. Regardless of ethnic dwellings, the Housing & Development Board (HDB) has built apartments throughout Singapore in order to ensure that government-led housing policies have been enforced due to lack of residence in the 1960s. But government also aims to maintain a multi-ethnic society that respects each other's life style. rather than having a complete melting pot of peoples.[4]

It does not have much difficulty in defining the expression 'community' or 'identity' in nation-state like Korea and Japan. But in Singapore, over a 700-year period, ethnic and cultural mixes have evolved into complex and colorful societies that make it difficult to extract a single feature.[5] This obscure intersection between the Malay Peninsula and the ethnic and racial aspects of Singapore was described by anthropologist Robert W. Hefner as "permeable(or penetrable) and canopied ethnicity."[6] Thus, this paper will look into Singapore's multi-ethnic society from the perspective of a relative boundary-based ethnic that is formed in the relationship between social inclusion and exclusion, as pointed out by Norwegian social anthropologist Frederik Barth.[7]

Lim Siam Kim, former head of the National Heritage Board of Singapore, who was in charge of the NHB Act, which was drafted in 1993, worked with the Oral History Centre(新加坡口述歷史中心) in Singapore. In an interview in 2016, he said, "the government decided it would assist the communities, which constitute the racial composition of Singapore, to set up their own heritage centres to promote their respective heritage."[8] So the Chinese Heritage Centre, Malay Heritage Centre, Indian Heritage Centre and Eurasian Heritage Centre were opened.

[2] Singapore Bicentennial Office, Singapore Bicentennial: From Singapore to Singaporean, 2019, p.9.

[3] Mathew Mathews, “Introduction: Ethnic Diversity, Identity and Everyday Multiculturalism in Singapore,” Mathew Mathews (ed.), The Singapore Ethnic Mosaic: Many Cultures, One People, World Scientific, 2018, p.xii.

[4] Barbara Leitch LePoer, “Introduction,” Barbara Leitch LePoer (ed.), Ibid., p.xxi.

[5] John Miksic, “Temasik to Singapura: Singapore in the 14th to 15th Centuries,” Karl Hack et als. (eds.), Singapore from Temasek to the 21st Century: Retinventing the Global City, NUS Press Singapore, 2010, p.104.

[6] Robert W. Hefner, The Politics of Multiculturalism: Pluralism and Citizenship in Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia, University of Hawaii Press, 2001, p.15.

[7] Frederik Barth, Ethnic Groups and Boundaries: The Social Organization of Cultural Difference, Boston: Little Brown and Company, 1969, p.15.

[8] Lee Tang Ling, “The Chinese Heritage Centre: Putting Singapore on the Diaspora Map,” Pang Cheng Lian (ed.), 50 Years of the Chinese Community in Singapore, World Scientific, 2016, pp.78-79.

3.Analysis of Exhibition Storytelling

As mentioned in the introduction, the exhibition goes through the process of storytelling by adjusting the order and the number of objects in consideration of the visitors' movement. The word 'storytelling' consists of three parts: story, tell and –ing. From the perspective of narratology, we can see the story as a kind of material that is not completed until it is told by a human. In the process of conveying this story, the story is finally born, after reconstruction, as a result of the delivery. When applied to the exhibition, the producer of the exhibition selects the story material with the 'concept' after the condensation of intent. He reprocesses it to create a story framework, and applies specific story styles to produce visible exhibition objects. The empathy is triggered by the consumers of the exhibition, interpreting and accepting the objects based on their personal and social context. Therefore, the application of narrative semiotics in analyzing exhibition communication is appropriate to reveal the intention and its interpretation.

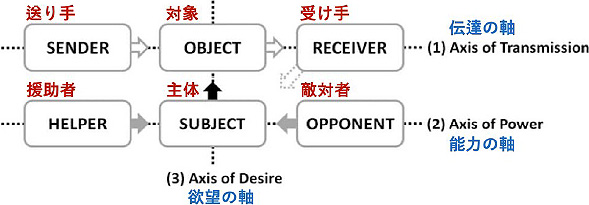

For example, the model of Cannonical Narrative Schema(物語の標準的図式), proposed by Algirdas J. Greimas, is a series of acts from initial state(最初の状態) to final state(最後の状態) that the protagonist(main character) goes through in three test(試練): qualifying test(資格を与える試練), decisive test(中心となる試練) and glorifying test(栄誉の試練). At each stage of test, the protagonist is required to satisfy these three phases after manipulation-contract(操作): competence(遂行能力), performance(遂行), and sanction(応報). We can abbreviate the process of the protagonist's transition from the initial state to the final state with an 'Actantial Model'(行為素モデル). By exploring and reflecting on the object that the main character pursues, he discovers the value contained in it and acts as an active subject rather than a passive message receiver. In this process, the subject gains an advantage over the opponent with the aid of helpers.[9]

The narrative analysis helps us to understand the mechanism of exhibition communication, either microscopically or macroscopically. First, to analyze the narrative strategy of individual exhibitions on a micro level, the Canonical Narrative Schema that explains the journey of the main character is useful. The exhibition creators set up a process to cultivate the literacy ability of viewers to find out the meaning of the object and finally to sympathize with the value. Singapore's ethnic heritage centres make visitors empathize with the collective identity of the community by identifying the hardships, adversity, fate and missions as a kind of test, and also by showing the process and examples of overcoming them with unbreakable will.

However, when comparing national museums in parallel on a macro level, the Actantial Model, which applies the element of confrontation between the subject and the opponent is helpful. This is because the exhibitions of each heritage centre do not simply denigrate or attack other ethnic community, but use a predominant strategy to conceal themselves that they are the best and superior in the society of Singapore. In an equally multi-ethnic society, it is not easy to prove that all ethnic groups have a similar orientation value and that the narratives of violent confrontation are hard to gain empathy. In order to occupy a better position than the competitors, they need to set up as if there is a hidden opponent actant by emphasizing the helper actant. By imagining an unspoken virtual competition, they can create an atmosphere in which their group can achieve superiority when each actantial model of ethnic communities collides.

The four Heritage Centres try to show off its superiority with putting up their own helper actant. First, the Chinese Heritage Centre (CHC) highlights the achievements of Chinese people who have maintained their cultural traditions and artistic attitudes in the Qing Dynasty to prove that they are the center of a 30 million Chinese network. Secondly, the Malay Heritage Centre (MHC) seeks to empathize with the religious center point of Islam by introducing the mission and journey of the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca. Third, the Indian Heritage Centre (IHC) builds a large, modern building and introduces luxurious and colorful exhibitions to emphasize the economic capabilities of the Indian community. Fourth, the Eurasian Heritage Centre (EHC) first reveals its diverse racial roots from various European countries, showing its weakness as a loose community. However, they use a dramatic strategy that transforms them into a strong sense of unity and responsibility by showing an active participant in the battle to protect Singapore during World War II.

[9] Algirdas J. Greimas, Sémantique structurale, Paris: P.U.F., 1966, 262 p.

4.Exhibition Strategy of Ethnic Museums in Singapore

Each Heritage Centre has the advantage of following this formula to complete the image strategy of voluntarily and independently overcoming the hard times. On the other hand, if the opponent actant is emphasized because of too much independence, the phase of performance and sanction of the narrative may be strengthened so that the composition of confrontation rather than harmony may be highlighted. The newly created Asian Civilization Museum (ACM), for example, was built in the downtown core area where Raffles first landed, and it is pledged that Southeast and South Asia exhibits will serve as a representative of its international region. It is also analyzed that the Peranakan Museum's intensive exhibition of the Chinese-based Peranakan only shows the intent of differentiation and pro-Chinaization by the Singaporean government, which sets the standard time zone to be the same as China, unlike other Southeast Asian countries.

Although the Chinese ethnic population occupies more than 70 percent, the constitutional language is Malay. The strategy of prominently favoring only one race, in the situation of using four official languages, can create tension between the subject and the opponent. When these tensions accumulate, integration at the horizontal and intercultural level may not be easy. Looking at the shadow of Singapore's multi-cultural policies aimed at horizontal exchange and coexistence among peoples, there is a concern that the multi-cultural policy of Korea and other asian countries raises the concern that we regards migrants as just helper or opponent actant without giving them any status as a subject actant in the society.

【References】

- Algirdas J. Greimas, Sémantique structurale, Paris: P.U.F., 1966, 262 p.

- André Desvallés & François Mairesse, Key Concepts of Museology, Arman Colin, 2010.

- Barbara Leitch LePoer (ed.), Singapore: A Country Study, Federal Research Division: Library of Congress, 1989.

- Edward J. McCaughan, “Race, ethnicity, nation, and class within theories of structure and agency,” Social Justice, Vol. 20 No. 1-2, 1993.

- Frederik Barth, Ethnic Groups and Boundaries: The Social Organization of Cultural Difference, Boston: Little Brown and Company, 1969.

- John Miksic & Cheryl-Ann Low Mei Gek (eds.), Early Singapore 1300s-1819: Evidence in Maps, Text and Artefacts, Singapore History Museum, 2005.

- Mathew Mathews (ed.), The Singapore Ethnic Mosaic: Many Cultures, One People, World Scientific, 2018.

- Robert W. Hefner, The Politics of Multiculturalism: Pluralism and Citizenship in Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia, University of Hawaii Press, 2001.